Obituary: William R. Tanskley (1939-2022), Former English Professor, LC Dean, Liberal Arts Advocate

Former Fordham English Professor, Lincoln Center Dean, and liberal arts advocate, William Ronald Tanksley, passed on January 7, 2022 at the age of 82. He was surrounded by loved ones in his residence at Red Hook, Hudson Valley.

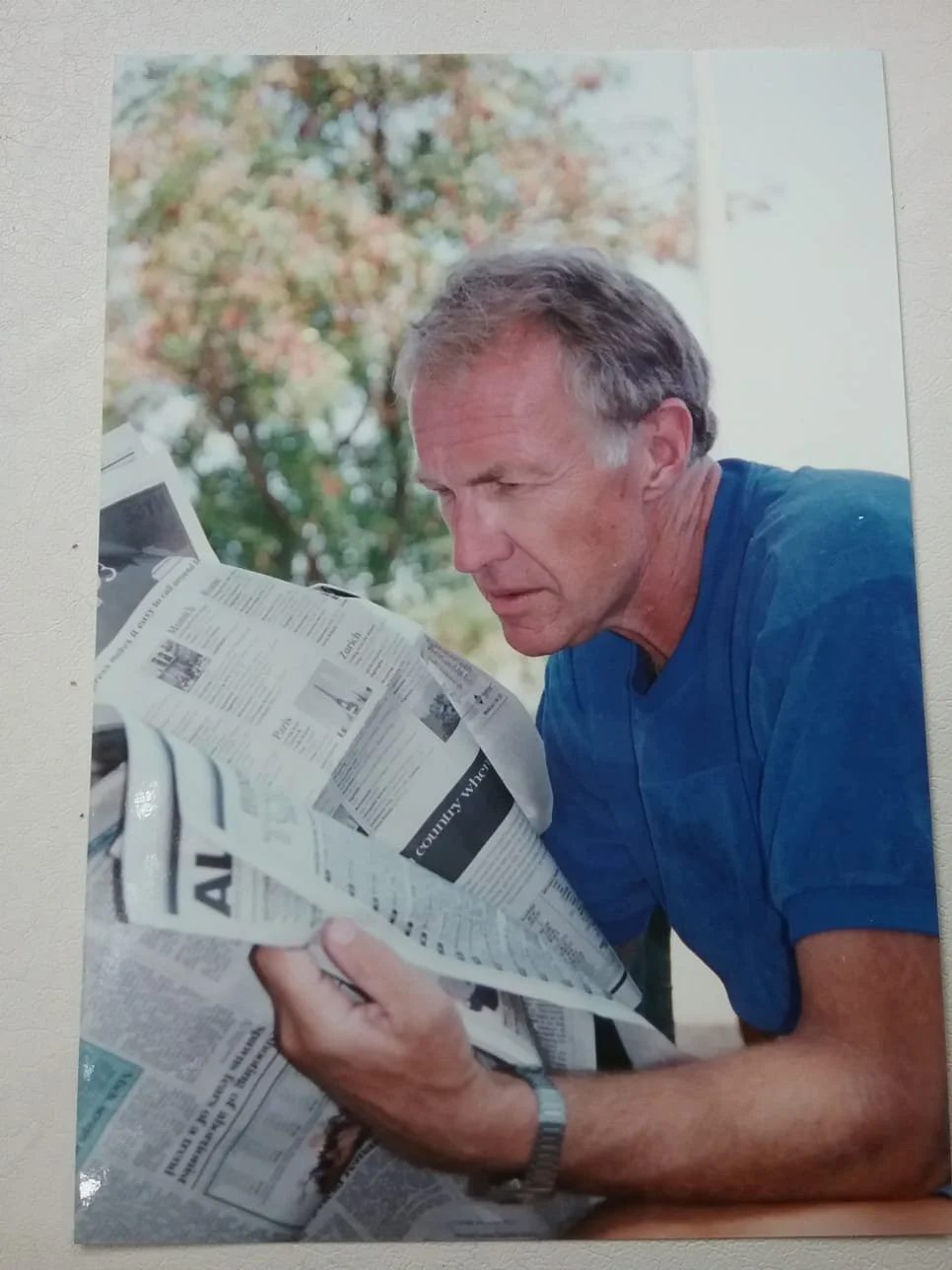

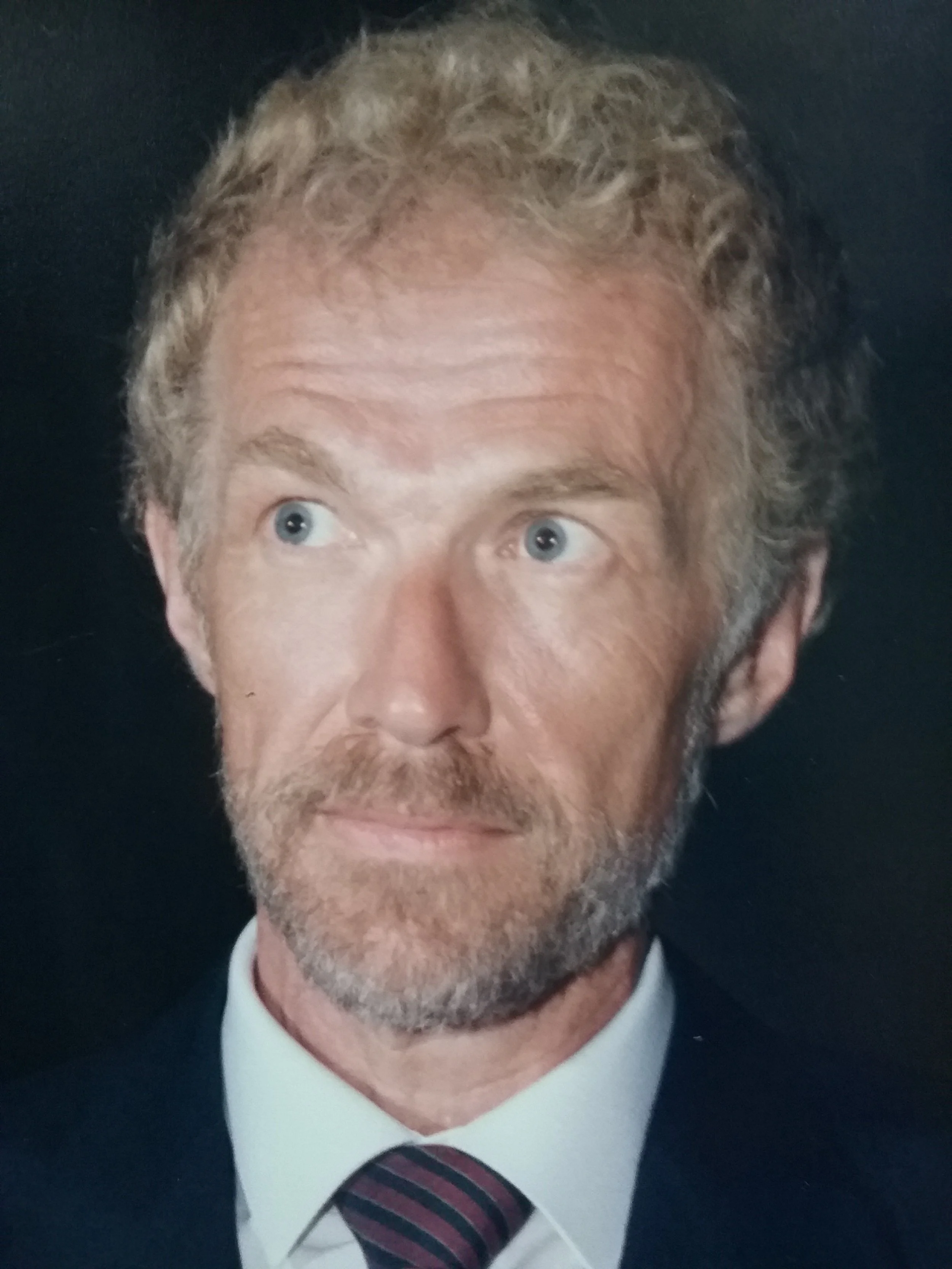

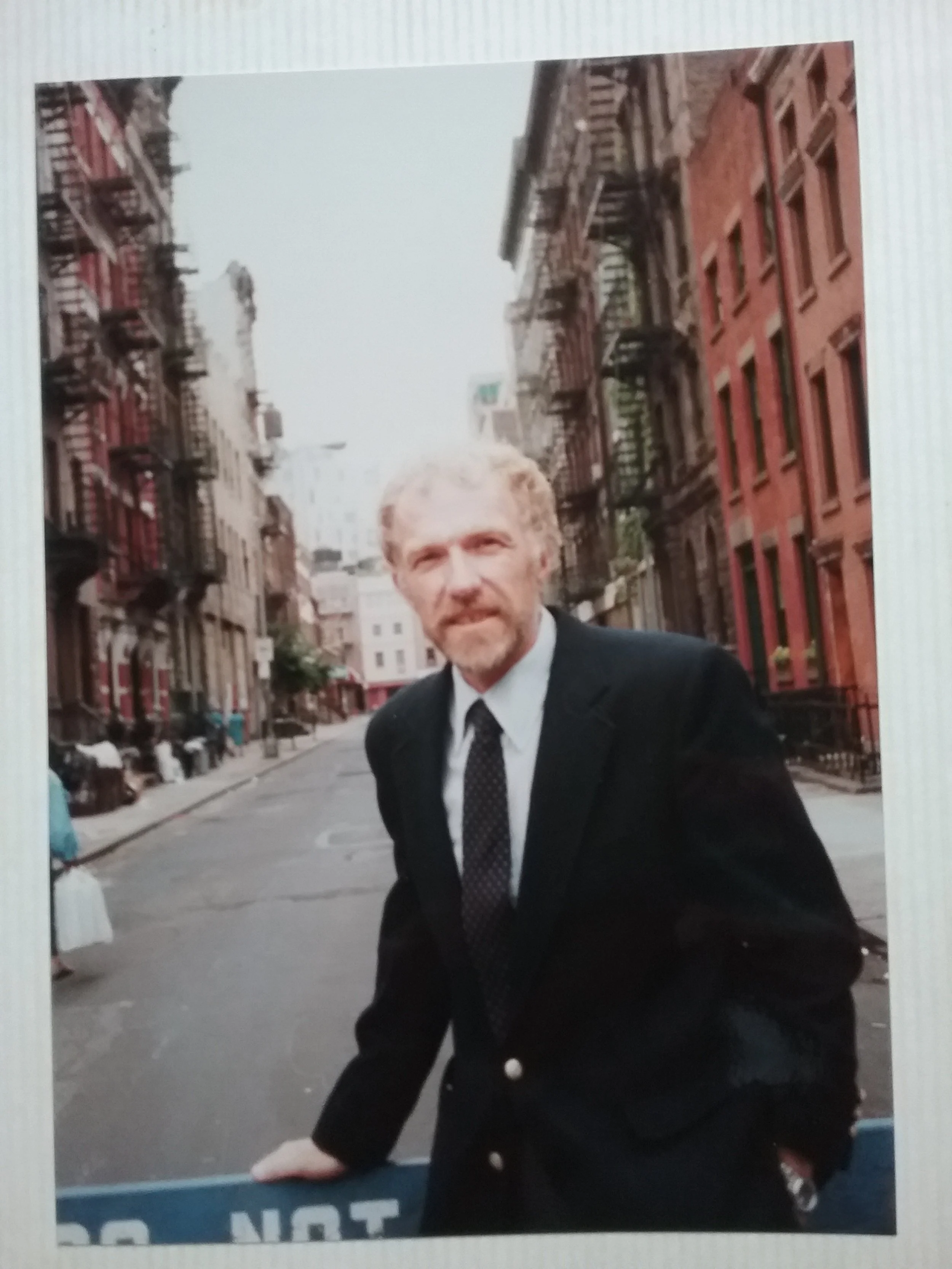

William R. Tanksley (Photos courtesy of Fulvia Masi.)

From Fall 1990 to Spring 2013 Professor Tanksley taught English courses, incorporating film and comparative literature into his syllabi alongside American literature. Comparative literature was his strength; beloved authors included Leo Tolstoy, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Italo Calvino, Jorge Luis Borges, Milan Kundera, Patrick Süskind, Thomas Pynchon, Richard Powers, and Richard Tarnas.

Tanksley was born on March, 27, 1939, in Spokane, Washington to parents Raymond and Frances Tanskely. He had two brothers who have also passed, Raymond Jr. Tanskley and Robert Tanskley. Tanksley tragically lost his first wife Elaine in a car crash in 1980, but their four children, Kristin, Kimberley, Wendy and Gregory, and Tanskley himself, survived. After marrying Fulvia Masi on July 7 1987, they had two children together, William and Mosa.

After graduating from Gonzaga University in 1963, he went on to complete his Masters and Doctorate degrees from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1969. In his early academic career, in an assignment that was very important to him, Tanksley spent two years (1972-74) at Idaho State University where he initiated and taught writing courses on the Fort Hall Reservation. He also spent two years (1978-80) as the Dean of the School of General Studies at Prahran College (now part of Deakin University) in Melbourne, Australia. During his tenure there, he submitted a proposal to Australian accreditation and funding authorities for a Bachelor of Arts program in Humanities and Social Sciences which was the most extensive program of its kind ever approved at that time in Australia.

His entire career as an administrator and as a teacher centered students , and it was this focal point that informed his advocacy of the liberal arts. “Liberal arts education,” he wrote, as part of his teaching philosophy, “affirms the interconnectedness of all the ways of knowing, reminding us that bridges connect more than embankments of a river. They raise questions of economics and of arts and politics; they change the social relationships between people on the two sides and also, perhaps, for good or bad, end the isolation (or innocence) of those on one side.”

William R. Tanskley

His wife, Fulvia Masi, says, “bridging across age, race, and culture was the goal of his life.” Masi was completing her dissertation at the School of Education when they met, and Tanskley’s secretary, Geri Owens, facilitated their communication. They married in Palermo in 1987 and lived in Woodstock, NY at the time. “All those trips from Manhattan to Woodstock, he always sang along to the radio,” says Masi. “He had a beautiful tenor voice, he played piano and listened to classical music. He also loved pop music and was always guessing who was going to become famous–he was right about Enya!”

Tanksley and Masi’s partnership extended to intellectual and literary collaboration. “We were so into each other’s coursework,” she remembers, “that we would exchange things. We also did team translations, Italian and English—we almost managed to convince Francesco Alberoni to have his book Valori translated into English, and translated a few chapters, but it fell through.”

Professor Leonard Cassuto, a colleague of Tanksley’s, remembers him fondly and says, "as long-suffering Knicks fans, Bill and I used to enjoy talking basketball during a long, tough time for our team."

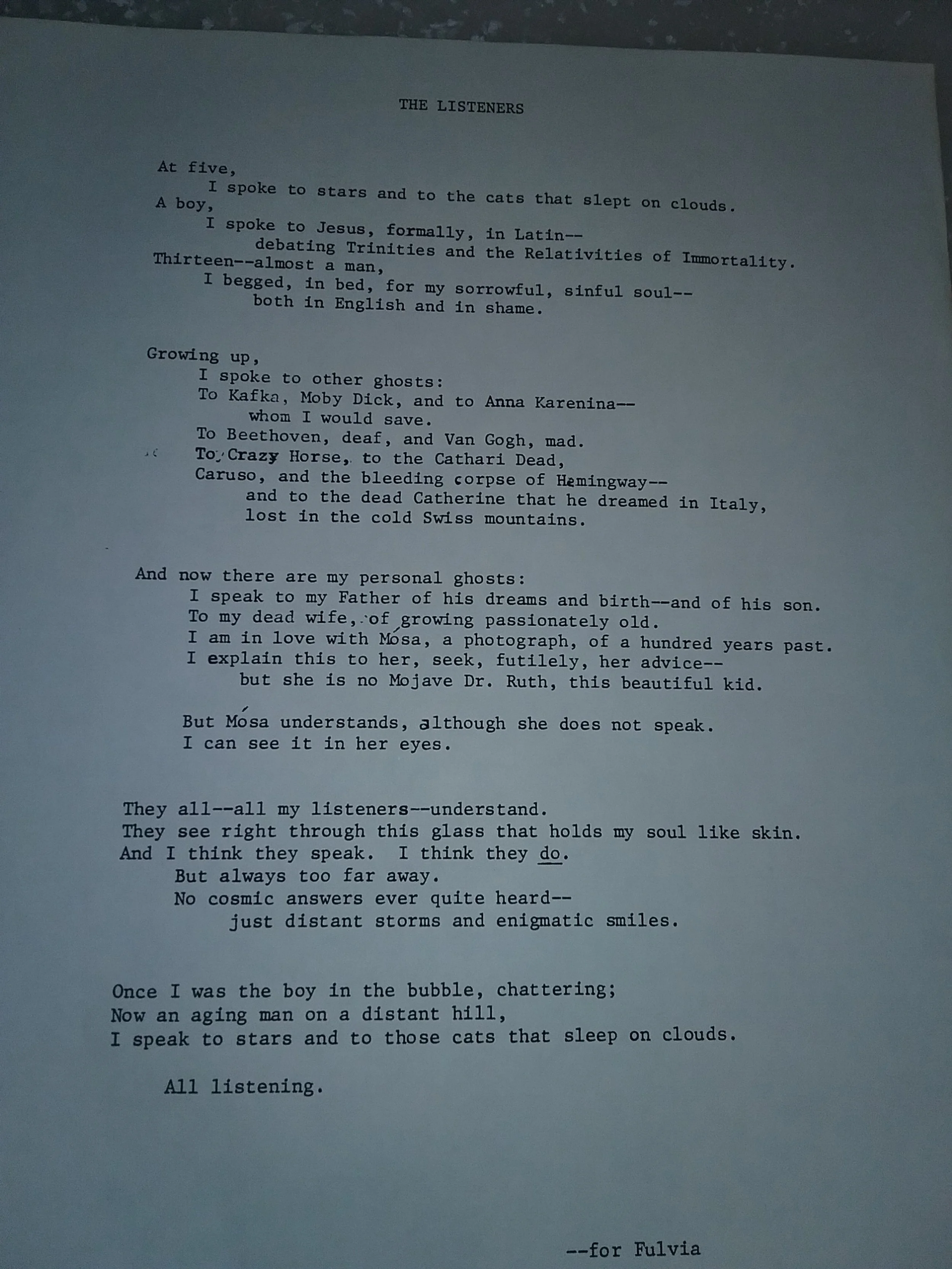

Tanskley is survived by his wife Fulvia Masi and their two children together, William and Mosa; four children, Kristin, Kimberley, Wendy and Gregory, from his first marriage to Elaine Tanskley; and a legacy of building bridges. A poem by Tanskley, “The Listeners,” written for his wife, follows.

William R. Tanksley in Manhattan

The Listeners

At five,

I spoke to stars and to the cats that slept on clouds.

A boy,

I spoke to Jesus, formally, in Latin--

debating Trinities and the Relativities of Immortality.

Thirteen—almost a man,

I begged, in bed, for my sorrowful, sinful soul--

both in English and in shame.

Growing up,

I spoke to other ghosts:

To Kafka, Moby Dick, and to Anna Karenina--

who I would save.

To Beethoven, deaf, and Van Gogh, mad.

To Crazy Horse, to the Cathari Dead,

Caruso, and the bleeding corpse of Hemingway--

and to the dead Catherine that he dreamed in Italy,

lost in the could Swiss mountains.

And now there are my personal ghosts:

I speak to my Father of his dreams and birth—and of his son.

To my dead wife, of growing passionately old.

I am in love with Mosa, a photograph, of a hundred years past.

I explain this to her, seek, futilely, her advice--

but she is no Mojave Dr. Ruth, this beautiful kid.

But Mosa understands, although she does not speak.

I can see it in her eyes.

They all—all my listeners—understand.

They see right through this glass that holds my soul like skin.

And I think they speak. I think they do.

But always too far away.

No cosmic answers ever quite heard--

just distant storms and enigmatic smiles.

Once I was the boy in the bubble, chattering;

Now an aging man on a distant hill,

I speak to stars and to those cats that sleep on clouds.

All listening.

--for Fulvia

A Poem, “The Listeners,” written by Tanksley for his wife Fulvia Masi